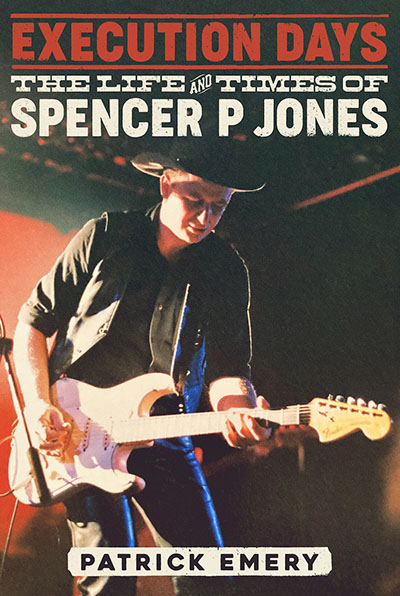

Execution Days: The Life and Times of Spencer P. Jones

Execution Days: The Life and Times of Spencer P. Jones

By Patrick Emery (Love Police)

Perhaps the most surprising thing about Melbourne writer Patrick Emery’s exhaustively researched and engrossing biography of the late Spencer P. Jones is that it found a publisher.

Thanks to the internet, book publishing is a low-margin crap shoot. But Aussie publishing houses were already renowned for their lack of imagination and reluctance to take risks on books about anyone who’s not mainstream, middle-of-the-road or, ahem, National Living Treasures. Even those imprints that are outgrowths of universities, our bastions of free thought.

If you haven’t received a formal rejection letter from a friendly Aussie publisher after shopping a musician’s autobiography, you haven’t lived. The stupidity of not keeping and framing a letter that read, in part, “there is no market for this because Radio Birdman fans can’t read” is regrettable in hindsight – it should have gone straight to the pool room - but, fuck you, anyway, self-important publisher twat. You deserve to be shot by a ball of your own shit.

Patrick Emery suffered his share of similar fools while trying to place “Execution Days”.

It’s doubtful that Love Police see their decision to pick it up as an act of public service, but it is and it should be lauded.

Suppose the declaration of interests should come here: The author is a long-tome contributor to, and friend of, the I-94 Bar, and the surviving members of Spencer’s old band The Johnnys have a professional association with your Barman.

Unlike Patrick, I didn’t know Spencer P. Jones very well. There were a few in-person encounters, and on one occasion he clearly wasn’t in great nick when he confided to someone that he barely knew that “I’m not doing heroin any more”. The solo gig that followed was shambolic and possibly more than a little cathartic.

Candour was Spencer’s strong point. He could loyal to a fault but also notoriously difficult for bandmates, managers, the disdained “industry” and his partners.

It would have been dead easy to play up the darker and more sensational sides of the book’s subject. That’s what publishers - and most of the public- want. Who hasn’t skipped the first 30 pages of a music bio and dived right into the tales of debauched sex, drugs and rock and roll?

Call me Walter Mitty but the trip through the gutter leading to the last rites of a band’s existence is much more interesting than waffle about a precocious kid being handed their first charity shop guitar.

Spencer’s is a terrific yarn and there’s not a jot of self-indulgence in its telling. This is a kid from New Zealand who wanted to make it in rock and roll in Australia. He bounced between bands, relationships and the odd day-job in Sydney and Melbourne, and the southern capital became his home.

Playing with Beasts of Bourbon, The Johnnys, The Gun Club on one side the street and Paul Kelly and Renee Geyer on the other is a formidable curriculum vitae. Spencer’s impact rippled through Europe where he toured with the Beasts, Shotgun Rationale and The Johnnys, and the USA, which he visited in company with Kelly and the Beasts. But there’s much more to the story.

Most people will pick this up because of Jones' founding association with the Beasts of Bourbon - and that's fair enough. If they'd been his only band, their tempestous, at times self-destructive and complex story would have sustained a book in its own right.

Melbourne’s Byzantine band linkages are arguably more complex than those of Sydney, and the ins and outs of which backing band Spencer held in favour and why he moved onto the next one during his purple patch of five studio albums on the Spooky and Beast labels with the likes of The Last Gasp, Cow Penalty and The Escape Committee are my highlights.

“Execution Days” is no “Please Kill Me”. Emery has resisted playing up the seamier side of his subject’s side - or applying varnish. He just tells it like it was. Spencer lived a dozen lives with drugs and alcohol both frequent features, but he was almost always about the music. That comes across, as does Emery’s keen ear, network of contacts and deep knowledge.

The pervading theme is the generosity and underlying kind nature of Spencer P. Jones, a friend to so many and a patron to so many more. Emery faithfully records Jones’ roles as a player, confidant, provocateur, role model and musical enabler.

There was a time in the 1990s when it was impossible to see a good band on a stage in Melbourne that didn’t boast Spencer as a member or supporter, and it’s related in fine detail.

Inevitably, there are errors. Ian Rilen wasn’t taken by liver cancer (bladder cancer was the culprit) and the line-up that played The Axeman’s Benefit in Sydney varied from the one billed (headliners the Hoodoo Gurus were more like the Hoodoo Duo), but these are relatively minor points.

Most stories are told from Spencer’s perspective (naturally enough) so some of the people involved will take issue with some facts. No matter. Corroboration was sought. It’s then a judgement call what to use.

There are 340-plus pages to absorb, previously unseen photos, many thrills and spills, lots of tragedy and comedy. This is a bloke who followed his muse rather than bend to seek security and commercial success. He sure did it the hard way at times. Did Spencer have regrets? Undoubtedly, but you get the impression they were more often personal than professional.

Justice done.